How To Cattle Interact With Wild Animals

Close-upwards of a dog during late-stage ("dumb") paralytic rabies. Animals with "dumb" rabies appear depressed, lethargic, and uncoordinated. Gradually they become completely paralyzed. When their pharynx and jaw muscles are paralyzed, the animals will drool and take difficulty swallowing.

Rabies is a viral zoonotic neuroinvasive disease which causes inflammation in the brain and is ordinarily fatal. Rabies, caused by the rabies virus, primarily infects mammals. In the laboratory it has been constitute that birds can exist infected, besides every bit cell cultures from birds, reptiles and insects.[1] Animals with rabies suffer deterioration of the encephalon and tend to comport bizarrely and ofttimes aggressively, increasing the chances that they will bite another animal or a person and transmit the disease. Most cases of humans contracting the disease from infected animals are in developing nations. In 2010, an estimated 26,000 people died from rabies, downward from 54,000 in 1990.[2]

Stages of disease [edit]

Three stages of rabies are recognized in dogs and other animals.

- The first stage is a ane- to three-twenty-four hours period characterized past behavioral changes[ specify ] and is known as the prodromal stage.

- The 2nd stage is the excitative phase, which lasts three to four days. It is this stage that is often known as furious rabies due to the trend of the affected creature to exist hyperreactive to external stimuli and bite at anything near.

- The 3rd stage is the paralytic or dumb stage and is caused past damage to motor neurons. Incoordination is seen due to rear limb paralysis and drooling and difficulty swallowing is caused past paralysis of facial and throat muscles. This disables the host's power to eat, which causes saliva to pour from the mouth. This causes bites to be the virtually mutual way for the infection to spread, as the virus is most full-bodied in the throat and cheeks, causing major contagion to saliva. Expiry is usually caused by respiratory abort.[iii]

Mammals [edit]

Bats [edit]

Bat-transmitted rabies occurs throughout North and South America merely it was beginning closely studied in Trinidad in the West Indies. This island was experiencing a significant price of livestock and humans alike to rabid bats. In the x years from 1925 and 1935, 89 people and thousands of livestock had died from it—"the highest human mortality from rabies-infected bats thus far recorded anywhere."[4]

In 1931, Dr. Joseph Lennox Pawan of Trinidad in the W Indies, a regime bacteriologist, found Negri bodies in the encephalon of a bat with unusual habits. In 1932, Dr. Pawan discovered that infected vampire bats could transmit rabies to humans and other animals.[5] [six] In 1934, the Trinidad and Tobago government began a program of eradicating vampire bats, while encouraging the screening off of livestock buildings and offering free vaccination programs for exposed livestock.

After the opening of the Trinidad Regional Virus Laboratory in 1953, Arthur Greenhall demonstrated that at least eight species of bats in Trinidad had been infected with rabies; including the common vampire bat, the rare white-winged vampire bat, as well as ii abundant species of fruit bats: the Seba's short-tailed bat and the Jamaican fruit bat.[7]

Recent information sequencing suggests recombination events in an American bat led the modern rabies virus to gain the caput of a G-protein ectodomain thousands of years ago. This modify occurred in an organism that had both rabies and a separate carnivore virus. The recombination resulted in a cantankerous-over that gave rabies a new success rate across hosts since the G-protein ectodomain, which controls binding and pH receptors, was now suited for carnivore hosts besides.[8]

Cats [edit]

In the United states, domestic cats are the most normally reported rabid animal.[9] In the United States, every bit of 2008[update], between 200 and 300 cases are reported annually;[x] in 2017, 276 cats with rabies were reported.[11] As of 2010[update], in every year since 1990, reported cases of rabies in cats outnumbered cases of rabies in dogs.[ix]

Cats that take not been vaccinated and are allowed access to the outdoors have the most take chances for contracting rabies, as they may come in contact with rabid animals. The virus is often passed on during fights between cats or other animals and is transmitted by bites, saliva or through mucous membranes and fresh wounds.[12] The virus tin can incubate from one day up to over a year before any symptoms begin to show. Symptoms have a rapid onset and tin can include unusual assailment, restlessness, lethargy, anorexia, weakness, disorientation, paralysis and seizures.[13] Vaccination of felines (including boosters) by a veterinarian is recommended to forestall rabies infection in outdoor cats.[12]

Cattle [edit]

In cattle-raising areas where vampire bats are common, fenced-in cows often become a principal target for the bats (forth with horses), due to their easy accessibility compared to wild mammals.[14] [15] In Latin America, vampire bats are the primary reservoir of the rabies virus, and in Peru, for case, researchers take calculated that over 500 cattle per year die of bat-transmitted rabies.[16]

Vampire bats have been extinct in the U.s.a. for thousands of years (a situation that may reverse due to climate change, as the range of vampire bats in northern United mexican states has recently been creeping northward with warmer atmospheric condition), thus United States cattle are not currently susceptible to rabies from this vector.[fifteen] [17] [18] However, cases of rabies in dairy cows in the United States has occurred (possibly transmitted by bites from canines), leading to concerns that humans consuming unpasteurized dairy products from these cows could be exposed to the virus.[19]

Vaccination programs in Latin America have been effective at protecting cattle from rabies, along with other approaches such as the culling of vampire bat populations.[16] [xx] [21]

Coyotes [edit]

Rabies is mutual in coyotes, and can be a cause for concern if they interact with humans.[22]

Dogs [edit]

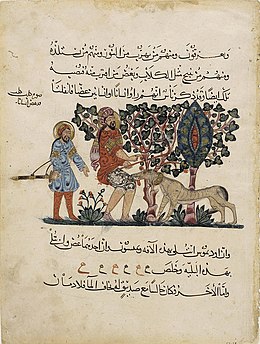

A folio from 1224 depicting a rabid domestic dog biting a human.

An epitome from 1566 depicting a group of men using an assortment of weapons to try and kill a rabid dog who is biting one of the men on the leg.

Rabies has a long history of association with dogs. The first written record of rabies is in the Codex of Eshnunna (ca. 1930 BC), which dictates that the owner of a dog showing symptoms of rabies should take preventive measure against bites. If a person was bitten by a rabid dog and later died, the owner was fined heavily.[23]

About all of the human deaths attributed to rabies are due to rabies transmitted by dogs in countries where domestic dog vaccination programs are not sufficiently adult to terminate the spread of the virus.[24]

Horses [edit]

Rabies can exist contracted in horses if they interact with rabid animals in their pasture, usually through being bitten (e.g. by vampire bats)[17] [15] on the muzzle or lower limbs. Signs include aggression, incoordination, head-pressing, circumvoluted, lameness, musculus tremors, convulsions, colic and fever.[25] Horses that experience the paralytic form of rabies have difficulty swallowing, and drooping of the lower jaw due to paralysis of the throat and jaw muscles. Incubation of the virus may range from 2–9 weeks.[26] Expiry often occurs within iv–five days of infection of the virus.[25] At that place are no effective treatments for rabies in horses. Veterinarians recommend an initial vaccination as a foal at iii months of historic period, repeated at one twelvemonth and given an annual booster.[25]

Monkeys [edit]

Monkeys, similar humans, tin can go rabies; however, they exercise not tend to be a mutual source of rabies.[27] Monkeys with rabies tend to dice more than speedily than humans. In one study, 9 of 10 monkeys adult severe symptoms or died within 20 days of infection.[28] Rabies is oftentimes a concern for individuals travelling to developing countries as monkeys are the most common source of rabies subsequently dogs in these places.[29]

Rabbits [edit]

Despite natural infection of rabbits being rare, they are peculiarly vulnerable to the rabies virus; rabbits were used to develop the first rabies vaccine past Louis Pasteur in the 1880s, and proceed to be used for rabies diagnostic testing. The virus is often contracted when attacked by other rabid animals and tin incubate within a rabbit for upward to 2–iii weeks. Symptoms include weakness in limbs, head tremors, low ambition, nasal discharge, and death within 3–4 days. There are currently no vaccines available for rabbits. The National Institutes of Health recommends that rabbits exist kept indoors or enclosed in hutches outside that practice not allow other animals to come in contact with them.[x]

Skunks [edit]

In the United States, in that location is currently no USDA-approved vaccine for the strain of rabies that afflicts skunks. When cases are reported of pet skunks biting a human, the animals are oft killed in social club to be tested for rabies. Information technology has been reported that iii different variants of rabies be in striped skunks in the north and southward central states.[10]

Humans exposed to the rabies virus must begin mail-exposure prophylaxis before the illness can progress to the key nervous system. For this reason, information technology is necessary to determine whether the brute, in fact, has rabies as apace every bit possible. Without a definitive quarantine period in place for skunks, quarantining the animals is non advised equally there is no way of knowing how long it may take the animal to show symptoms. Devastation of the skunk is recommended and the brain is then tested for presence of rabies virus.

Skunk owners have recently organized to campaign for USDA approving of both a vaccine and an officially recommended quarantine period for skunks in the U.s.a..[ citation needed ]

Wolves [edit]

Under normal circumstances, wild wolves are generally timid around humans, though there are several reported circumstances in which wolves take been recorded to act aggressively toward humans.[30] The majority of fatal wolf attacks accept historically involved rabies, which was kickoff recorded in wolves in the 13th century. The primeval recorded example of an actual rabid wolf set on comes from Germany in 1557. Though wolves are not reservoirs for the disease, they can grab it from other species. Wolves develop an uncommonly severe aggressive land when infected and tin can bite numerous people in a unmarried assault. Before a vaccine was developed, bites were virtually always fatal. Today, wolf bites can be treated, but the severity of rabid wolf attacks can sometimes result in outright death, or a bite most the caput will make the disease act also fast for the treatment to have effect.[30]

Rabid attacks tend to cluster in winter and leap. With the reduction of rabies in Europe and Due north America, few rabid wolf attacks have been recorded, though some all the same occur annually in the Middle East. Rabid attacks tin can be distinguished from predatory attacks by the fact that rabid wolves limit themselves to bitter their victims rather than consuming them. Plus, the timespan of predatory attacks tin sometimes last for months or years, as opposed to rabid attacks which end usually after a fortnight. Victims of rabid wolves are unremarkably attacked around the head and neck in a sustained manner.[30]

Other placental mammals [edit]

The about usually infected terrestrial animals in the U.s. are raccoons, skunks, foxes, and coyotes. Whatever bites by such wild animals must be considered a possible exposure to the rabies virus.

Most cases of rabies in rodents reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the U.s.a. have been found among groundhogs (woodchucks). Small rodents such every bit squirrels, hamsters, republic of guinea pigs, gerbils, chipmunks, rats, mice, and lagomorphs similar rabbits and hares are almost never found to be infected with rabies, and are not known to transmit rabies to humans.[31]

Marsupial and monotreme mammals [edit]

The Virginia opossum (a marsupial, different the other mammals named above, which are all eutherians/placental), has a lower internal body temperature than the rabies virus prefers and therefore is resistant but non allowed to rabies.[32] Marsupials, along with monotremes (platypuses and echidnas), typically accept lower body tempertures than similarly-sized eutherians.[33]

Birds [edit]

Birds were outset artificially infected with rabies in 1884; however, infected birds are largely, if not wholly, asymptomatic, and recover.[34] Other bird species have been known to develop rabies antibodies, a sign of infection, after feeding on rabies-infected mammals.[35] [36]

Transport of pet animals between countries [edit]

Sign at a Britain port showing rabies prevention measures aimed at merchant sailors.

Rabies is owned to many parts of the world, and one of the reasons given for quarantine periods in international animal transport has been to try to keep the disease out of uninfected regions. However, most developed countries, pioneered past Sweden,[ citation needed ] at present allow unencumbered travel between their territories for pet animals that have demonstrated an adequate allowed response to rabies vaccination.

Such countries may limit move to animals from countries where rabies is considered to exist under control in pet animals. At that place are various lists of such countries. The Uk has developed a list, and France has a rather unlike list, said to be based on a list of the Office International des Epizooties (OIE).[ citation needed ] The European Spousal relationship has a harmonised list. No listing of rabies-costless countries is readily bachelor from OIE.[ original research? ]

In recent years, canine rabies has been practically eliminated in North America and Europe due to extensive and often mandatory vaccination requirements.[37] However information technology is still a significant problem in parts of Africa, parts of the Eye East, parts of Latin America, and parts of Asia.[38] Dogs are considered to exist the main reservoir for rabies in developing countries.[39]

Even so, the contempo[ when? ] spread of rabies in the northeastern United States and further may cause a restrengthening of precautions against movement of possibly rabid animals between developed countries.[ citation needed ]

See also [edit]

- Prevalence of rabies

- Rabies manual

- Rabies vaccine

Footnotes [edit]

- ^ "CARTER John, SAUNDERS Venetia - Virology : Principles and Applications – Page:175 – 2007 – John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England – 978-0-470-02386-0 (HB)"

- ^ Lozano R, Naghavi Chiliad, Foreman Thousand, Lim South, Shibuya Yard, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Adair T, Aggarwal R et al. (Dec fifteen, 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of decease for xx age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Report 2010" (PDF). Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30050819. PMID 23245604. S2CID 1541253.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ Ettinger, Stephen J.; Feldman, Edward C. (1995). Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine (4th ed.). W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN978-0-7216-6795-9.

- ^ Goodwin and Greenhall (1961), p. 196

- ^ Pawan (1936), pp. 137-156.

- ^ Pawan, J.L. (1936b). "Rabies in the Vampire Bat of Trinidad with Special Reference to the Clinical Class and the Latency of Infection." Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology. Vol. 30, No. 4. Dec, 1936.

- ^ Greenhall, Arthur M. 1961. Bats in Agriculture. Ministry of Agriculture, Trinidad and Tobago.

- ^ Ding, Nai-Zheng; Xu, Dong-Shuai; Sun, Yuan-Yuan; He, Hong-Bin; He, Cheng-Qiang (2017). "A permanent host shift of rabies virus from Chiroptera to Carnivora associated with recombination". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 289. Bibcode:2017NatSR...7..289D. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-00395-2. PMC5428239. PMID 28325933.

- ^ a b Cynthia M. Kahn, ed. (2010). The Merck Veterinary Transmission (10th ed.). Kendallville, Indiana: Courier Kendallville, Inc. p. 1193. ISBN978-0-911910-93-3.

- ^ a b c Lackay, S. N.; Kuang, Y.; Fu, Z. F. (2008). "Rabies in small animals". Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 38 (4): 851–ix. doi:ten.1016/j.cvsm.2008.03.003. PMC2518964. PMID 18501283.

- ^ "Rabies Vaccination Cardinal to Prevent Infection - Veterinary Medicine at Illinois". Academy of Illinois Higher of Veterinary Medicine . Retrieved 2019-12-15 .

- ^ a b "Rabies in Cats". WebMD . Retrieved 2016-12-04 .

- ^ "Rabies Symptoms in Cats". petMD . Retrieved 2016-12-04 .

- ^ Bryner, Jeanna (2007-08-15). "Thriving on Cattle Blood, Vampire Bats Proliferate". livescience.com . Retrieved 2019-10-28 .

- ^ a b c Carey, Bjorn (2011-08-12). "Start U.S. Death by Vampire Bat: Should We Worry?". livescience.com . Retrieved 2019-10-28 .

- ^ a b Benavides, Julio A.; Paniagua, Elizabeth Rojas; Hampson, Katie; Valderrama, William; Streicker, Daniel G. (2017-12-21). "Quantifying the brunt of vampire bat rabies in Peruvian livestock". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. eleven (12): e0006105. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0006105. ISSN 1935-2735. PMC5739383. PMID 29267276.

- ^ a b "Do vampire bats really exist?". USGS . Retrieved 2019-10-28 .

- ^ Baggaley, Kate (2017-10-27). "Vampire bats could shortly swarm to the United States". Popular Scientific discipline . Retrieved 2019-10-28 .

- ^ "Rabies in a Dairy Moo-cow, Oklahoma | News | Resource | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2019-08-22. Retrieved 2019-x-28 .

- ^ Arellano-Sota, C. (1988-12-01). "Vampire bat-transmitted rabies in cattle". Reviews of Infectious Diseases. 10 Suppl 4: S707–709. doi:10.1093/clinids/10.supplement_4.s707. ISSN 0162-0886. PMID 3206085.

- ^ Thompson, R. D.; Mitchell, G. C.; Burns, R. J. (1972-09-01). "Vampire bat control by systemic treatment of livestock with an anticoagulant". Science. 177 (4051): 806–808. Bibcode:1972Sci...177..806T. doi:10.1126/scientific discipline.177.4051.806. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 5068491. S2CID 45084731.

- ^ Wang, Xingtai; Dark-brown, Catherine M.; Smole, Sandra; Werner, Barbara M.; Han, Linda; Farris, Michael; DeMaria, Alfred (2010). "Aggression and Rabid Coyotes, Massachusetts, USA". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 16 (two): 357–359. doi:10.3201/eid1602.090731. PMC2958004. PMID 20113587.

- ^ Dunlop, Robert H.; Williams, David J. (1996). Veterinary Medicine:An Illustrated History. Mosby. ISBN978-0-8016-3209-nine.

- ^ "Rabies and Your Pet". American Veterinary Medical Association . Retrieved 2019-12-15 .

- ^ a b c "Rabies and Horses". www.omafra.gov.on.ca . Retrieved 2016-12-04 .

- ^ "Rabies in Horses: Brain, Spinal Cord, and Nerve Disorders of Horses: The Merck Manual for Pet Health". world wide web.merckvetmanual.com . Retrieved 2016-12-04 .

- ^ "Diseases Transmissible From Monkeys To Human being - Monkey to Human Bites And Exposure". www.2ndchance.info . Retrieved 2016-12-04 .

- ^ Weinmann, E.; Majer, M.; Hilfenhaus, J. (1979). "Intramuscular and/or Intralumbar Postexposure Treatment of Rabies Virus-Infected Cynomolgus Monkeys with Human Interferon". Infection and Immunity. American Society for Microbiology. 24 (1): 24–31. doi:10.1128/IAI.24.1.24-31.1979. PMC414256. PMID 110693.

- ^ Di Quinzio, Melanie; McCarthy, Anne (2008-02-26). "Rabies risk among travellers". CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association Periodical. 178 (5): 567. doi:10.1503/cmaj.071443. ISSN 0820-3946. PMC2244672. PMID 18299544.

- ^ a b c "The Fearfulness of Wolves: A Review of Wolf Attacks on Humans" (PDF). Norsk Institutt for Naturforskning. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-02-xi. Retrieved 2008-06-26 .

- ^ "Rabies. Other Wild fauna: Terrestrial carnivores: raccoons, skunks and foxes". 1600 Clifton Rd, Atlanta, GA 30333, Us: Centers for Illness Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2010-12-23 .

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ McRuer DL, Jones KD (May 2009). "Behavioral and nutritional aspects of the Virginian opossum (Didelphis virginiana)". The Veterinarian Clinics of N America. Exotic Animal Practise. 12 (ii): 217–36, viii. doi:10.1016/j.cvex.2009.01.007. PMID 19341950.

- ^ Gaughan, John B.; Hogan, Lindsay A.; Wallage, Andrea (2015). Abstruse: Thermoregulation in marsupials and monotremes, chapter of Marsupials and monotremes: nature's enigmatic mammals. ISBN9781634834872 . Retrieved 2022-04-20 .

- ^ Shannon LM, Poulton JL, Emmons RW, Woodie JD, Fowler ME (April 1988). "Serological survey for rabies antibodies in raptors from California". Periodical of Wild animals Diseases. 24 (ii): 264–7. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-24.2.264. PMID 3286906.

- ^ Gough PM, Jorgenson RD (July 1976). "Rabies antibodies in sera of wild birds". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 12 (3): 392–5. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-12.3.392. PMID 16498885.

- ^ Jorgenson RD, Gough PM, Graham DL (July 1976). "Experimental rabies in a slap-up horned owl". Journal of Wild animals Diseases. 12 (3): 444–seven. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-12.3.444. PMID 16498892. S2CID 11374356.

- ^ "Administration of Rabies Vaccination State Laws". www.avma.org . Retrieved 2016-12-04 .

- ^ "Rabies:Introduction". The Merck Veterinary Manual. 2006. Retrieved 2007-08-14 .

- ^ Rupprecht, Charles E. (2007). "Prevention of Specific Infectious Diseases: Rabies". Traveler'southward Health:Yellow Book. Centers for Disease Command and Prevention. Archived from the original on 2007-08-14. Retrieved 2007-08-fourteen .

References [edit]

- Baynard, Ashley C. et al. (2011). "Bats and Lyssaviruses." In: Advances in VIRUS RESEARCH Volume 79. Research Advances in Rabies. Edited by Alan C. Jackson. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-12-387040-7.

- Goodwin One thousand. Thou., and A. M. Greenhall. 1961. "A review of the bats of Trinidad and Tobago." Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 122.

- Joseph Lennox Pawan (1936). "Transmission of the Paralytic Rabies in Trinidad of the Vampire Bat: Desmodus rotundus murinus Wagner, 1840." Almanac Tropical Medicine and Parasitol, 30, April viii, 1936, pp. 137–156.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rabies_in_animals

Posted by: parkerowle1997.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How To Cattle Interact With Wild Animals"

Post a Comment